By Tess GC

“I see a desire, whether or not we’re aware of it, for real liberation instead of band-aids.” I wrote this last week at the end of my piece “The Pandemic’s Capitalist Feminism,” and I’ve been thinking about why this feels true – that we’re entering a period where enough people are fed up with bullshit passed off as feminist liberation that we could see a real return of a robust feminism. This feminism could grapple with the conditions of our lives as working people, living under an economic system that requires shoring up, with our lives and blood, while it enters a period of some of the most intense extractions of wealth in recent memory, from the workers upward to the owners.

I want to make a case that those of us inclined to write and talk about the exploitation of women, queer people, and even men under patriarchy should really start to consider what it would mean to encourage a return of the feminist lens that’s stronger than we’ve seen it before – that’s consciously combatting the forces that are hurting everyone, and that’s rejecting the milquetoast, top-down feminism that comes out of the white, middle class nonprofit world, and posits itself as feminism for everyone. As Raechel Anne Jolie writes, “a lot of people think feminism is whatever ‘feminist nonprofits’ are up to, and nonprofits are counter-revolutionary forces that inevitably squash structural change.” Essentially, I want to make a case for a class conscious, anti-capitalist feminism, one that holds the best principles from the fights for an intersectional feminism, led especially by women of color, working class women, queer and trans women, and others relegated to the margins of white, comfortable women’s feminism.

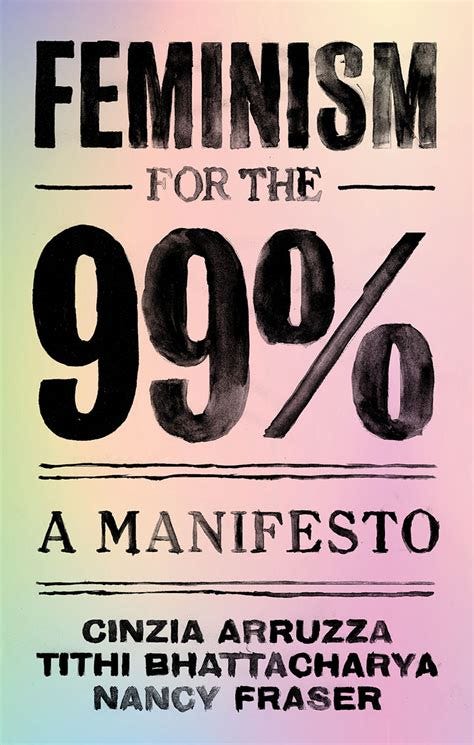

What a class conscious feminism could do is bring together the critiques of white feminism, nonprofit feminism, girlboss feminism, and other half-assed versions into a robust movement or lens, united and ready to ride the wave of the increasing working class, anti-capitalist consciousness that’s sweeping the country as union membership and drives rapidly increase, and a critical mass of us can no longer afford rent, healthcare, groceries, and children. As the authors of the 2017 manifesto, “Feminism for the 99%” write: “this iteration of capitalism has raised the stakes for every social struggle, transforming sober efforts to win modest reforms into pitched battles for survival.”

What happened to feminism for the 99%?

This 2017 manifesto, “Feminism for the 99%,” included prominent socialist feminist thinkers in its authorship like Angela Davis, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, Nancy Fraser, Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya, and Barbara Ransby (most of these are academics, if they don’t sound familiar to you). After the manifesto’s success, it was published as a book in 2019. In 11 sections, Feminism for the 99% explains how “What we are living through is a crisis of society as a whole – and its root cause is capitalism.” Its authors are writing about what a renewed feminism needs to be like to actually combat women’s problems now.

I remember Feminism for the 99% coming out, and its publication coincided with the election of Trump to the presidency, the Women’s March, and a whole host of marches and protests that really didn’t do much aside from register discontent, and produce a whole lot of “in this house we believe” yard signs. Nice thoughts, but ineffective when it came to actually combating the increase in fascist capitalism. Feminism for the 99% was an alternative to these largely ineffective protestations against Trump, prescribing international women’s movements against capitalist patriarchy, and feminism that centers the most exploited. It calls for recognizing women as workers in the capitalist machine, and as the majority of people performing reproductive labor – that is, unpaid labor to carry, give birth to, and raise the next generation of workers.

As I started to write this piece, I wondered, what the heck happened to Feminism for the 99%? I heard about it a lot when it first came out, and haven’t really since. They’re talking about pretty much exactly what I’m trying to bring up – a renewed feminism that’s class conscious, and for and by the working people.

Feminism for the 99% made a crucial interjection into the pre-pandemic feminism that was consumed with girl boss feminism, Sheryl Sandberg’s “lean in” corporate feminism, and “liberal feminism,” which in their words, “asks ordinary people, in the name of feminism, to be grateful that it is a woman, not a man, who busts their union, orders a drone to kill their parent, or locks their child in a cage at the border” (2). Inspired by mass women’s strikes in 2017 and 2018 across the world, the authors wrote the manifesto after they saw the liberal, corporate feminism of elites in the U.S. failing – in their words, “[Hillary] Clinton's defeat is our wake-up call. Exposing the bankruptcy of liberal feminism, it has created an opening for a challenge to it from the left” (4). Between then and now, we had a massive global pandemic, and as I wrote in my previous article, “[the pandemic] caused a distinct break in a lot of our social movements.”

It’s both a huge bummer and kind of cool to realize that Feminism for the 99% was the intervention we needed like seven years ago, and it’s still what we need today – I think the authors of Feminism for the 99% were right on when they were writing in 2017. Their message might have been a little early for the times, or they were just unlucky with the pandemic, but I really want their points to be revived in light of the conditions as they are now – and those conditions are even more stark than they were before the pandemic. The beefing up of the social safety net that we saw during the pandemic has been almost entirely stripped back, while economic conditions for working people are markedly worse than pre-pandemic times.

The origins of our patriarchy

In 2004, academic Silvia Federici released a book called Caliban and the Witch. In Caliban, Federici convincingly ties the rise of witch hunts in Europe to the point that capitalism began to form as the dominant economic system. She identifies the roots of the type of subjugation that women experience under capitalism as having emerged then. Federici’s insights are crucial to understanding the patriarchy we live within – and what kind of feminism can actually subvert it instead of becoming co-opted by it.

Federici explains how in late medieval Europe, around the 13 and 1400s, the transition from feudalism to capitalism was brought about by the tactics that lords, merchants, and the Catholic Church (the ruling class, essentially) used to quell peasant rebellions against feudalism. A combination of factors led to peasants’ power causing real problems for the nobles during this period: peasant communities that tended to be more communal than what we live in today in the U.S. (protecting some peasants from exploitation); drastically reduced population numbers in Europe due to conflict and plague (giving peasants real power to refuse the will of their lords, and use their labor as a bargaining chip); and new waves of religious thought that allowed questioning of the Catholic Church’s supremacy (this is the Protestant Reformation). Federici writes that “by the end of the 14th century, the revolt of the peasantry against the landlords had become endemic, massified, and frequently armed” (25).

The ruling class responded to peasant revolts with tactics and practices of repression that would become the calling cards of the capitalist system. Chief among these tactics was privatizing large swaths of communal land that peasants relied on to survive, called the enclosure of the commons. By controlling access to land and resources for survival, nobles forced more and more of the peasantry off their lands, into the growing cities, and into becoming workers who were reliant on wages from the ruling and owning class to survive.

In Caliban, while Silvia Federici talks about the myriad of tactics the nobles used to regain control, her main purpose is to explain how modern patriarchy was one of these tactics. It’s no coincidence that the witch hunts arose during this period of emerging capitalism. This modern patriarchy emerged with the demonization of women. In particular, women who were accused of being witches were often old and poor (whose land could be claimed by the emerging state, once they were convicted), or, were those who had power in their communities, either because they were looked to for decision-making, or because they possessed knowledge of the human body and remedies (and were often the first stop for abortifacients).

Through witch hunts, communities were cleansed of powerful people, rebellious people (often women), and people with the knowledge to maintain peasant communities’ independence from the emerging power and knowledge consolidation of the elites. The subjugation and demonization of women, and particularly knowledgeable and powerful women, gave women’s fathers, husbands, and families control over women’s reproductive power, and power in general – and handed the reins of patriarchy to everyday men. In essence, this tactic broke the solidarity of the peasant laboring classes by turning to peasant men to subjugate women, enforce birth rates, and take over the sphere of knowledge creation, and particularly knowledge about reproduction and medicine. Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English’s 1972 pamphlet “Witches, Midwives, and Nurses” is an excellent, short overview that expands on this topic, as they write, “total control of medicine means potential power to determine who will live and who will die, who is fertile and who is sterile, who is ‘mad’ and who is sane” (2).

Of course, capitalist patriarchy wasn’t the only tactic to break the solidarity of the laboring classes with one another. Silvia Federici pays special attention to the ruling class’s creation of racial categories, the ones we know today. In this period, the emerging nation states of Europe set off to colonize other lands to find new sources of free and exploitable labor (African slaves and Indigenous peoples), and resources to resupply their coffers and fuel their wars against one another (I really recommend the book Racecraft, on capitalism and the creation of racial categories by Barbara and Karen Fields). The connection between women’s exploitation to this outgrowth of capitalism meant more and more people were now the targets of capitalism’s extraction – and enslaved and Indigenous women were vulnerable to exploitation from multiple fronts. Federici powerfully explains the origins of our exploitations, what we have in common with one another, and therefore the solidarity we must find with each other once again:

“The political lesson that we can learn from Caliban and the Witch is that capitalism, as a social-economic system, is necessarily committed to racism and sexism. For capitalism must justify and mystify the contradictions built into its social relations – the promise of freedom vs. the reality of widespread coercion, and the promise of prosperity vs. the reality of widespread [destitution] – by denigrating the ‘nature’ of those it exploits: women, colonial subjects, the descendants of African slaves, the immigrants displaced by globalization” (17).

And to this I would add, all poor and working class people, no matter their gender or race, who get in the way of the capitalist machine – although men were given control over the autonomy of women, they themselves were and have been subject to the oppressions and villainization of the ruling class when they don’t serve its ends. It’s a deal with the devil.

Rejecting the master’s tools

In “Witches, Midwives, and Nurses,” Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English say: “To know our history is to begin to see how to take up the struggle again.” The feminist struggle has been so fraught for so long – so wracked by problems of wealth and class, racism, exclusion, desperate bids to hold the reigns of power that free so few, and liberate no one. In the United States, our inheritance is the problems of Europe, and by digging back through the European creation of the economic system that would come to rule our world, we find the origins of our problems today.

In 1979, thinker Audre Lorde said at a feminist conference: “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change. And this fact is only threatening to those women who still define the master’s house as their only source of support.” I think this moment where I see a lot of women and queer people pushing back against industries that have been exploiting us, like beauty and fashion; or questioning the so-called liberation of giving up close social bonds in the name of careers that didn’t give back to us; or wondering together again and again what it means that feminism is so captured by pop stars and giant media corporations – this moment is THE time to insist that these questions are ones that have everything to do with the origins of our common struggles. It’s the time to be serious about what kind of politics might move us toward liberation, instead of toward the next little adjustment that will run its course a few years from now.

Caliban and the Witch is a story that begs us to draw the lines from the origins of our problems to those problems today – discourse about birth rates, abortion, and gender; private property and the commons, and fights about who gets to own and control land and resources; Christian right wing nationalists, the upholders of the ruling class’s war on us; the legacy of colonization in the United States and the imperialism and colonization our country now enacts on others; racist, classist, and sexist demonization of one another that distracts from the class war being waged on all of us by elites; and simply the ruling class’s control of what is real knowledge, real history, and reality itself. These are all questions that the book Feminism for the 99% percent addresses, but more simply, that a feminism for the 99%, a class conscious feminism, an anti-capitalist feminism, a feminism that rejects the master’s tools is capable of taking on.

Related links

-The Pandemic’s Capitalist Feminism

-girl culture panic and the failures of feminism by

-Witches, Midwives & Nurses: A History of Women Healers

-Burning Women: The European Witch Hunts, Enclosure, and the Rise of Capitalism

-Racecraft: The Soul of Inequality in American Life

-Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation

-It’s Expensive to be a Man by

-Men, we should join the fight for abortion

Such a thorough and helpful synthesis of this necessary literature. And thanks for the shoutout🖤

I'm currently reading Rethinking Feminism by bell hooks - which is a great critique of 2nd wave white liberal feminism - and she has practical suggestions in response to the ways the movement failed to connect with men and working class women. It's a very grounded analyses with ideas for doing better.