By Tess GC

All around Substack, Youtube, and various social medias, I’ve been seeing the question directly and indirectly asked – what is the state of feminism in 2024? This summer in the United States, a celebration and commentary on femininity swirled around in pop culture. Barbie premiered, Taylor Swift and Beyoncé toured the country, Olivia Rodrigo released a new album – it was a summer of sparkles, metallics, and pink in pop culture. This fall and winter have been distinctly gray toned, at least in my online world, mostly influenced by the genocide in Gaza, and its interconnections with imperialism, capitalism, and climate change. I mean, someone self-immolated a few days ago in protest of the genocide in Gaza. It’s intense, it’s bleak, it’s feeling pretty desperate. We’re also four years into a global pandemic. It caused a distinct break in a lot of our social movements, and pushed many of us further online in droves, and in ways unseen before.

The juxtaposition between the summer of femininity and the winter of genocide is an interesting one that we can use to look at the raw material of coping under patriarchy – and specifically we know that when we talk about patriarchy, we’re talking about it within the context of also living under capitalism, in a world structured around white supremacy, awash with transphobia, and that marginalizes people along the lines of ability, age, etc. While all of these interconnected issues bear renewed analysis and conversation in 2024, I see in my world right now the makings of a resurgence of conversation about feminism. Some of the dominant social conversations about femininity, feminism, and patriarchy are reaching more clarity as the world around us feels like it’s spiraling faster and faster, and the coping mechanisms that capitalist patriarchy offers us are no longer allaying our fears and insecurities, but making many of them worse. As these copes or reforms to patriarchy are starting to lose their luster this winter, I think we’re in a moment where we can begin to see a renewed, more radical class-conscious feminism emerging from the consumptive frenzy of the last few years.

The resurgence of conversation about femininity is just one corner of a larger conversation about the state of the feminist movement, but it helps us explore the forces buffeting everyone around under patriarchy. Writer Raechel Anne Jolie, writing under the Substack, radical love letters, recently wrote a great piece called “girl culture panic & the failures of feminism.” In it she writes about the feminist “waves.” She identifies the present moment “as arguably…a fifth wave, which is an extension of the fourth wave, but in a post-Trump, post-#MeToo, post-George Floyd, pandemic world.” Third and fourth wave feminism, as she explains, dealt more with issues of identity and intersectionality, and choice, than previous waves. Jolie also writes that:

“most versions of feminism that we have today do not have actually radical aims, even if the people involved are discursively critical of systems like capitalism and white supremacy…feminism has been [quickly and easily] co-opted because it’s not inherently interested in interrogating the root causes of systems of domination, especially if we continue to place its origin in a voting movement that occurred in the midst of chattel slavery and not long after violent colonial displacement.”

Like Jolie says, how radical feminism is depends on where you’re grounding your feminism, and as Jolie notes, contemporary feminism is overwhelmingly rooted in these ideas of feminist ‘waves’ that begin with white, upper crust women demanding the right to vote. It certainly is true that most popular feminism now is not ‘radical,’ is not working to interrogate larger systems of oppression. I want to look at a few topics that have been prevalent in the last couple years in popular conversations about feminism, and that have offered a real mixed bag of reformist feminist solutions to our problems – bandaids on the wounds whose real cause are deeper, more systemic problems. These topics are choice, desirability, and consumption, and by examining them more, we can dig out the more radical impulses of feminism that I think are (re)emerging. Within them, we can see how the individual choice feminism of the third wave that still dominates American feminism may have finally begun to overplay its hand, as I hope we enter a period ripe for a renewed, radical, class-conscious feminism.

Choice feminism

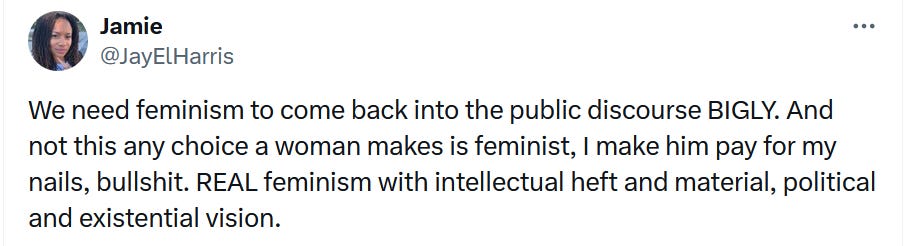

Not long after I started thinking about writing this piece, my partner sent me this post on X, which made me certain other people are also noticing or hoping for a more robust feminism to emerge. The poster, Jamie Lynn Harris, @JayElHarris says: “We need feminism to come back into the public discourse BIGLY. And not this any choice a woman makes is feminist, I make him pay for my nails, bullshit. REAL feminism with intellectual heft and material, political and existential vision.” During the pandemic, a consumption-based choice feminism became hyper-concentrated in my online world, and I know it did in many others’ as well. In “girl culture panic & the failures of feminism” Raechel Anne Jolie says, “I don’t know how much value there is in feminism as a coherent movement anymore” pointing to how many people are alienated from its focus on women, while more and more people identify outside the gender binary, its ongoing problems with whiteness, its cooptation by exploitative nonprofits, its treatment of sex workers, and “when it too often colludes with the state rather than envisioning ways of being outside and against it.” These critiques are important to continue to consider, especially as Jolie advocates feminism as a lens more than a movement in and of itself. Both @JayElHarris and Jolie note the need for feminism that moves away from individual and capitalist choice, choice usually meaning the privileged or the powerful get to make decisions about their autonomy and well-being while everyone else is left with no choices, or bad ones.

“The personal is political” is a phrase formulated during second wave feminism. At its best, it points us toward our experiences being interconnected with the structural problems we’re all living with. At its worst, “the personal is political” is concerned primarily with the issues of middle and upper class women, and has come to mean, ‘I can do politics through my consumer and lifestyle choices’ – or as one of my friends (@mariannerart on Patreon) said recently, by doing “politics as a personality trait.” How we modify, decorate, and present our bodies, how they then give us social and economic capital, and how we consume to achieve desired outcomes have been questions haunting my thoughts for the last few years, because these questions haunt our advertising, our social media feeds, our conversations with each other. These topics aren’t actually new, but I do think the pandemic brought on a new era, a new hyper-fixation with them, that in turn is leading to cracks in their monopoly on our lives.

Hot girls and the limits of the individual

First is an example that might not mean much to those who aren’t fairly online, or pretty young: the “hot girl.” A hot girl, or being in your “hot girl era” really spread into our lexicons after being popularized by rapper Megan Thee Stallion in her 2019 song with Nicki Minaj, “Hot Girl Summer” – and subsequently spread across the internet, taking a little break during the first year of the pandemic maybe, but emerging just as strong in the next couple years. A “hot girl era” basically means a conscious turn toward doing what you want without societal permission, and many people use it in a gender-neutral way. Doing your hot girl era is fairly individualistic, it’s about your personal choices, but at its best it’s also an empowering message that tells girls, women, queer people, you define what is desirable and what makes you feel like a cool, hot girl doing your thing. Unfortunately, the hot girl message runs into the problem of the message versus the messenger – the people who get the most traction talking about a hot girl era are overwhelmingly conventionally attractive women whose content does way better and goes more viral than people who aren’t conventionally attractive, not to mention those who have the means and ability to do what they want, when they want. And what is considered conventional attractiveness is pretty much a standard set by the patriarchy we live within.

As more and more of us are queer, there’s a general idea that we’re also beginning to “queer” attractiveness – that is, that queer people are socially redefining what’s attractive. I think there’s some truth to this, but capitalist patriarchy always swoops in to capitalize on the narratives of liberation – and suddenly we’re surrounded by messages that were once meant to empower everyone, coming from the mouths of beautiful, rich people that most of us will never actually look like or be privileged like.

And then there’s corporate and business capitalization on these trends toward personal empowerment, trying to sell us stuff to change ourselves to feel better about ourselves, under the guise of ‘being our best selves,’ which incidentally involves spending money to be different than we actually are. The problem with choice feminism is that it’s so easily corrupted and sold back to us, dressed up in our supposed liberation. I don’t want to demonize every type of choice feminism, because a lot of times it feels like it’s better than nothing – but it doesn’t change the rule book at all, it just gives us a little more room to edit the patriarchal rules. We can do our best to be cool and hot, which incidentally often involves spending a lot of money and changing our bodies, but attaining those statuses are fickle, always changing, and will always require a new look, a new personality, youth, and so many other qualities that ultimately keep us scrambling and keep us oppressed. (This article by Jessica Defino includes some references to this).

On the topic of attractiveness, myself, my friends, and many women on the internet have noticed more conversations on our feeds around plastic surgery, botox, and anti-aging. I’ve become increasingly aware of celebrities’ use of subtle procedures to look more ‘glamorous’ and look ageless year after year, while I’ve been seeing more and more content on my feed discussing these procedures, and even advertising them to me. I also started paying a lot more attention to my own anti-aging skincare during the pandemic, wearing sunscreen diligently every day, using retinol, and finding myself considering new products that promise to “fix” all kinds of new skin problems I didn’t know I had. Jessica Defino discusses the scam of anti-aging serums and creams in her column, telling us that most products, even those recommended for anti-aging by many dermatologists, aren’t actually doing much to make us look younger over the years.

When it comes to the uptick in advertising botox and plastic surgery to average consumers, many people, women especially, have been discussing these noticeable changes. It’s been fascinating to watch more progressive women vacillate between knowing that these trends are ultimately not helping any of us, and not wanting to critique other women. I’ve heard quite a few iterations of, “I’m not saying these things are bad, I’m not trying to shame anyone who chooses to do this, you do you…” At the same time, the glaring realities of racism, classism, ageism, ableism, and just straight up sexism and misogyny in the sudden mainstreaming of these procedures, specifically among cisgender women, speak for themselves.

Within these conversations, it seems the best any of us can do is say “I’m making x choice for myself, but I won’t make a judgment on what others choose.” However, there’s a really difficult conversation to be had about how our personal beauty and anti-aging choices affect everyone else. Jessica Defino, who formerly worked in the beauty world, does a great job with this in her Substack newsletter. Her tagline in this piece reads: “Can we have everlasting youth *and* empowerment? How anti-aging ideology disempowers the collective.” Defino is willing to state, straight out, that each of our individual buy-ins to patriarchal, capitalist beauty standards do affect everyone else. And she’s right. I think we need to begin the beauty participation conversation with the assumption that we do, in fact, affect one another. From there, we can have better conversations about what is to be done, given that reality. Other voices that I’ve found interesting in this conversation are in video essays by Jordan Theresa (and another here), Mina Le, Tiffany Ferg, and Shanspeare on Youtube (Note that these are all young people in their 20s — this article would have been aided by including more older voices in my examples).

Consumption and choice

Choice and personal “empowerment” within feminism are also tightly linked with consumption, which the pandemic supercharged for many people. Pre-pandemic, we already had conversations going about how expensive it is to pay for the trappings of “femininity,” but this question became even more prominent as the pandemic era gave birth to faster trends across many consumer products, and in my world extremely noticeably for feminized products, particularly fashion and home decor and wares. While there’s plenty to be said about how products men tend to consume are less scrutinized than everyone else’s consumption, there’s also no denying that the influx of ever-cheaper products for the person and the home, especially spurred on by an intensified era of dropshipping, are heavily targeted at those who make many of the decisions about what kinds of products make their way into the home – those who do the majority of domestic labor.

I’ve seen some thoughtful pushback against our collective increase in consumption, particularly when accusations of sexism have arisen when anyone critiques the over-consumption of products that women tend to buy. This article, “no, calling out hyperconsumption is not sexist” does a good job of explaining how in the realm of consumption, feminism, femininity, and women’s interests have been hijacked by capitalism. The author, Clara, writes that under this capitalist idea of feminism, “This notion of consumption — not of relationships, of community, of experiences, but of products — [is] the ultimate arbiter of femininity and womanhood.”

While pandemic era femininity – and feminism – have been so marked by consumption, and dissatisfaction grasping desperately at empowerment, I think the beginnings of serious push back are emerging in this gray winter we’ve been in, and I think we need to grab onto these impulses and push them forward as much as we can. In my online world in particular, I’m seeing more and more women and queer people critiquing systems instead of each other, and asking one another to think critically about how we engage in those systems without blaming and shaming the individual.

A largely online movement I’ve found really interesting that blends personal choice with some degree of structural understanding is the no buy/low buy phenomenon. The idea is that many people already have all the things we need and more, and that to break our reliance on regular shopping to provide dopamine, we try purchasing nothing but essentials, or limiting our non-essential purchases. This winter saw a dramatic surge in people (mostly women) participating and documenting their journeys on social media. No and low buys are a great vehicle for a more political consciousness to begin, making more people who begin to be aware that our world is flooded with cheap goods that are killing the planet, while we’re addicted to shopping, can’t afford the things we really need (housing, healthcare), and want to find meaning in our lives through more than consuming. This movement still relies on individual consumer choices, but choosing to opt out of consuming is markedly different than choosing which products to buy – and opens the door for reflection on the system itself, which is much more easily politicized than merely conscious consumerism is.

Bringing about a return of robust feminism, either as a movement or a lens, will be like any other organizing – finding out where people are at in their lives, what’s hurting them, and using the moments and movements that are drawing people in to raise a consciousness about the deeper roots of these problems. I really think there’s potential for a renewed feminism, brought about by our coping mechanisms for patriarchy, our reforms running out of steam lately. I see people, led by women and queer people, connecting with nature, writing, making art, calling themselves artists and creatives, working with their hands, reclaiming the creative labor whose value was stolen from us by industrialization and the mainstreaming of cheap goods (see Angela Davis, Women, Race, and Class). I see a desire, whether or not we’re aware of it, for real liberation instead of band-aids.

Next week I’ll explain this class conscious feminism I see emerging, and some hopes for its direction.

Thank you as always Tess! I've studied feminist theory pretty intensely (my degree is in Women, Gender and Sexuality studies) and so I'd just like to add to this conversation that feminism was never inherently a coherent movement. "Liberal feminism"- the barbie, pink washed kind, with a history in the first wave voting movement centered in white supremacy- has always dominated in the mainstream because it's center left, making it pretty close to center right, so lots of people upholding status quo are happy with it. But radical feminism as a theory (which although I define as someone with radical viewpoints, I don't identify with radical feminism, because I don't actually agree with many of the theory's perspectives- a major one from Andrea Dworkin being that all heterosexual sex is r*pe) exists alongside socialist/marxist feminism, black feminism, ecofeminism-which is what I mostly identify with-, etc... I think a lot of people who don't really understand feminism see the barbie stuff and go "oh yeah, that's feminism", but it's such a grain of sand on the beach. The book "Feminist Thought" by Rosemarie Purnam Tong presents a good analysis of all this, for anyone interested. <3

Do you think that the overturning of Roe, losing bodily autonomy in many states, travel bans for pregnant people, increased homicide rates for pregnant people and people who just gave birth, etc etc etc are going to push people towards a more robust understanding of feminism and more radical political action? Christian extremist seem surprised by how strong, albeit underprepared, the resistance by voters and the culture has been to the most recent assaults on reproductive rights.