By Ben Stegbauer and Tess GC

Last week, our alma mater, Union Theological Seminary, became one of the first academic institutions to fully divest from companies profiting from the Israeli military. While Union is only one small school, it’s a great example for other institutions — and it shows the power of student movements.

While a lot of conversation has gone around the internet about the outbreak of student protests this spring, it seems time to move into a conversation about sustaining movements. The last few years have seen a real eruption of social movements, from protest and organizing for Black Lives in 2020, to the wave of union organizing, to the renewal of the fight for Palestinian liberation. As the U.S. aids Israel’s destruction of Gaza, it’s no longer a question of getting people to do something, but of channeling moments of protest and anger into movements that can mobilize and organize people for the long term, and win.

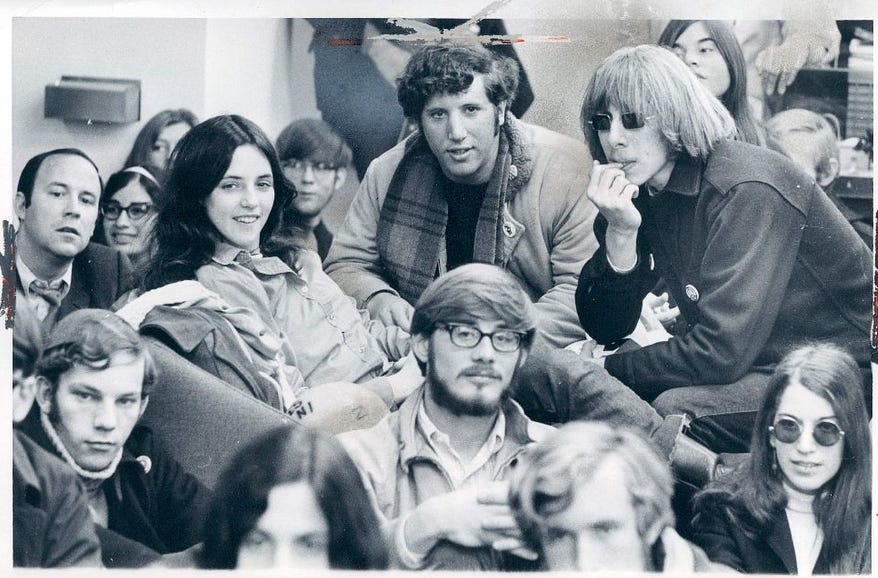

In this spring of 2024, we’ve encountered a flash point once more, as students have reignited the months-long fight for Palestine in encampments and protests on university campuses across the country. In March, the first 2024 university encampment began at Vanderbilt University, and others followed. Columbia University in New York quickly became major news, as students occupied the quad demanding transparency from the university about its donors and investments related to Israel and the military industrial complex. Police response was outsized and vicious. Students across the country escalated, setting up encampments and occupying buildings, from Cal Poly Humboldt to UCLA, and across the sea to Paris and Oxford. As the student protests have pushed Palestine back into the general public’s consciousness, people have been quick to point out the similarities between 2024 and the student anti-Vietnam War protests of the 1960s and ‘70s, particularly Columbia’s protests in 1968.

As students are reaching into their own histories of protest to put pressure on genocide supporters, the rest of us should take notes. And while campus protests are great, for those of us who aren’t students, or aren’t near a university encampment to support, what can we do?

Since October, the struggle for Palestinian liberation has shown how much we need in-person, community infrastructure to meet the tasks of liberation activists – such as the capacity to actually pull off a general strike. Looking to the 1960s and ‘70s, we can find some valuable blueprints for this infrastructure in three general categories: unions of all kinds; political organizations; and solidarity based community organizations with ties to one another.

Unions and the Peace Movement of the 1960s

The history of labor unions in the 1960s is multifaceted, especially when we put front and center their relationship to the anti-Vietnam War student movements. The struggles between Labor and other kinds of organizing in the 1960s and ‘70s can teach us about the power of – and need for – widespread labor organizing now. In “Organized Labor and the Vietnam Antiwar Movement,” author Jason Long shows first and foremost the reality that unions have never been singular nor monolithic. In the ‘60s, then-leader of the AFL-CIO, George Meany, refused to endorse any anti-war program. Over time, this refusal created a rift between union leaders and members, especially after the Tet Offensive in 1967, which saw greater public disapproval of the United States investment in the war. Some have speculated that this rift led to less collective power for unions throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

However, this was not the only story when it comes to Labor’s relationship to activism. Under president Walter Reuther, the United Auto Workers (UAW) supported progressive organizing, and even created the short-lived (as per Reuther’s death in 1970) Alliance for Labor Action in conjunction with the Teamsters. Outside of the major unions, the 1968 student movement also birthed the first iterations of Graduate Student Worker Unions (GWSU). It was during an anti-draft sit-in at UC Berkeley that talk of a GSWU began. This led to the University of Wisconsin-Madison becoming the first GSWU to win a contract in 1970. In the past couple years there seems to have been a resurgence in student workers’ unions. In California this has led to the UAW 4811, which represents University of California Graduate Students, holding a strike authorization vote this week (5/13-15) in response to UCLA calling the LAPD on their protest, and UCLA’s failure to protect students from counter-protest violence. Thus, the graduate student unions that were birthed out of the anti-war movement can now put more direct pressure onto colleges and the economy as a whole to divest from Israel, and to include Boycott, Divest, and Sanctions (BDS) as part of union contracts.

Even though the anti-war movement eventually brought some student workers themselves into union membership, the anti-war student movement of 1968 that represented an emerging “New Left,” and the established labor movement, now called the “Old Left,” definitely clashed. One conflict erupted in what is known as the Hard Hat Riots of 1970, in which 400 union construction workers attacked student anti-war protesters in downtown Manhattan. Nixon tried to cash in on this moment and gain support among the working-class by stoking divides between protesters and organized labor. While there was some working-class support for the Vietnam War (as well as middle-class support), that support began to dwindle by the late 1960s.The rift between the working-class and the student movement was decidedly more about class conflict than anything else. University students were portrayed as middle-class draft dodgers – and when they dodged the draft it was working-class kids who had to go to war instead. The class tensions that divided the student movement and the working-class was the primary barrier to solidarity, not support or resistance to the Vietnam War.

Today, media and elected officials paint the student movement as an upper- and middle-class movement, mimicking the tactics of the 1960s and ‘70s to divide working people. The media insists on focusing their attention on encampments at Ivy League schools, like Columbia and Yale, places already prone to resentment from the working-class, instead of focusing on the encampments at schools with more working-class accessibility, like Cal-Poly Humboldt or City College of New York. How do we wrestle with this impure history of class tensions, and move forward to create more coalitions of the anti-war working-classes? With the middle-class disappearing, we need more people in unions, and we need those unions to be places of connection and coalition building for student movements, as some are beginning to be.

Political and Community Organizations

Political organizations help the Left funnel ideals into direct engagement with the laws, policies, and governance that shape our lives. The pitfalls of a two-party center-right political system define some of the Left’s aversion to electoral politics today. However, one of our most successful interventions into electoral politics in the past decade has been the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), recruiting and running candidates at all levels of local, state, and federal government. While the DSA didn’t formally emerge until the 1980s, the socialist infrastructure that organized students and young people in the 1960s and ‘70s, providing infrastructure for student anti-war protests and organizing, would eventually birth the DSA. Although this era of young Left organizing saw an incredible amount of disagreement and splintering among its ranks, it laid the foundations for thinking through how the Left engages with political parties – whether that’s in running our own candidates, or in building relationships with the social and political organizations that can exert influence on electeds and policy – like unions.

Other examples that we see less of today are community organizations that also exert political and social influence. We need community organizations with organizing heft and vision, beyond paid organizers following a professional organizing model. Community organizing is most successful when it’s led by people who are doing it because they have to, not because they’re being paid to do it.

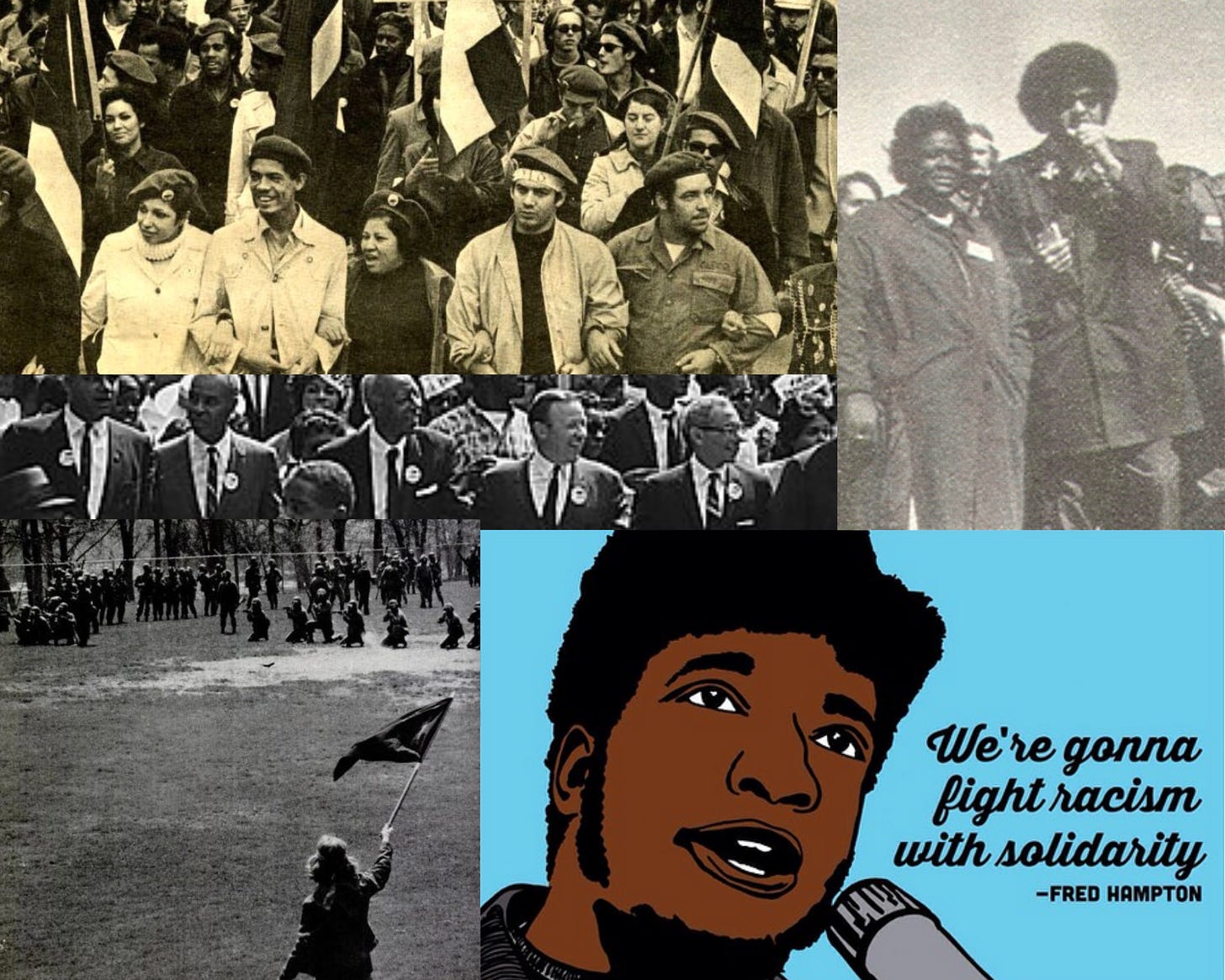

In the 1960s and ‘70s, working class groups like the Black Panthers, Young Lords, Young Patriots, Brown Berets, and the American Indian Movement gave marginalized people organizing infrastructure, allowing them to directly engage community problems, and to work and be in solidarity with other groups with shared aims. One example of this solidarity is the Rainbow Coalition, first founded in Chicago in 1969 by leaders of the Black Panthers, Young Patriots, and Young Lords, including Panther leader Fred Hampton. The Rainbow Coalition explicitly drew these groups together around their common economic oppression, aiming to lift each community. The coalition crumbled due to police harassment, and the police murder of Fred Hampton.

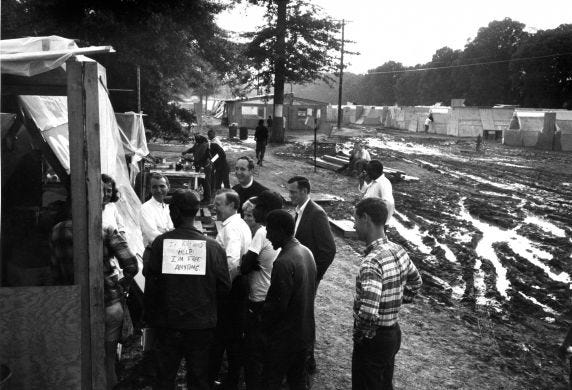

Many of these identity based organizing groups were the next generation’s response to the Civil Rights Movement’s successes and failures. While young radicals organized in groups like the Panthers, the first iteration of the Poor People’s Campaign (PPC) is where some established Civil Rights activists began to pivot their energy after they saw the shortcomings of the movement in enforcing racial equality, and addressing economic exploitation. Aiming to take on the economy through the “triple evils,” militarism, racism, and poverty, the Poor People’s Campaign was kneecapped before it could become fully fledged, as one of its key leaders, Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in 1968 just months before the PPC could rally its constituent groups in Washington, D.C. Despite King’s death, poor people went to D.C. anyway, organized with help from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Over the course of May 1968, 3,000 people occupied the National Mall, naming their encampment Resurrection City. Notably, Walter Reuther of the UAW sent funds to help sustain the encampment, and visited Resurrection City alongside members of the UAW’s Political Action Committee.

Like the Rainbow Coalition, the Poor People’s Campaign was a real attempt at a coalition movement – and while King gets a lot of credit for it, much of its coalitional, economic-based program came from people who had been doing anti-poverty work for a while, notably the leaders of the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO), many of them black women organizers. The Poor People’s Campaign was also distinctly multiracial – not only did it include poor black Americans, the leaders deliberately built coalitions with the leaders of other poor folks such as Native American, Puerto Rican, Asian-American, white Appalachian, Chicano, and farm worker organizers and activists. Its example showed the possibility of organizing in multiracial, economic coalitions, and a second iteration of the Poor People’s Campaign began in 2017.

What makes the Rainbow Coalition and the first iteration of the Poor People’s Campaign worth our study is how they organized people of different persuasions into solidarity coalitions. The Rainbow Coalition drew together mostly urban, young radicals interested in direct action and organizing to change the world in the present. The Poor People’s Campaign, created with the nonviolent principles of the Civil Rights Movement, brought disparate groups together, not necessarily united in ideology, but united in critique of the economic system hurting everyone. We need both of these options to organize people today – places where the farther Left can organize; places where people, regardless of ideology, can organize around economic conditions; and we need infrastructure to bring them together.

Looking to Our Communities

The present and the future are and will be disruptive and chaotic. This much we know. But all is not lost, and we already have examples today that bring together the successes of past organizers in new movements. Tenants’ unions bring together unionism, community organizing, and political action around the country, as they defend their members from evictions, raise political consciousness, and take legislative action like banning and limiting Airbnbs, and influencing local elections. The mutual aid groups that took off around the country during the pandemic can and are being transitioned into organizing infrastructure for community defense and rapid response to people’s immediate needs. The DSA has provided a model for fielding candidates in the two-party system, and figuring out how to elect candidates around the country with progressive, economic populism. It’s an ongoing conversation, how to keep these candidates accountable to the platforms they ran on.

In the end, it makes sense these student movements and encampments are happening on college campuses that have social infrastructure to bring people together. The condensed housing and meeting spaces combined with quasi-shared schedules creates an environment more conducive for movements to be birthed. It seems like a far off dream to think of people beyond university students having lives that lend themselves to this kind of organizing. But we can start, and if we want to be involved in the fight for a free Palestine, each and every one of us can jump into the waves of union organizing, progressive economic electoralism, and building community organizations by the people. Young students can remember how it feels to collectivize care, food, and culture, and demand it for the future instead of the alienated life in a studio apartment they can’t afford. We are living in an important moment right now, and it seems like we can all do something to help make sure this movement stays afloat long into the future.

Brilliant piece, thank you!